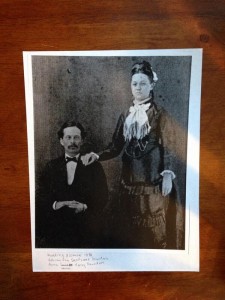

Last year my mother sent me some photocopied archives about my grandma’s family history compiled by my late great aunt, who had an avid interest in genealogy. My grandma’s and great aunt’s grandfather, Adrian Van Santvoordt Saunders (A.V.S. as he was known in his writings) was an imposing judge who lived and worked in Fort Morgan Colorado, east of Denver in the late 1880s. In 1876, he married my great great grandmother, Anna Laura Henry. That same year they traveled east to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, which was the first world’s fair to be held in the United States. In the archives my mother sent, A.V.S. had written about his experience at the 1876 exposition.

“In 1876 Mamma (Anna) and I went to the Worlds Fair in Philadelphia and while there Graham Bell had up a telephone in the Agricultural building—the sending and receiving were about 600 ft. apart—Mamma asked me to go to the other end and see if I could hear her voice and I did and heard her fairly plainly. Then she went and listened and she became enthused and talked of the great possibilities. I said it was merely a very clever plaything. She and the inventor, Mr. Bell had animated conversation over the matter at different times for several days. Since then I have often thought how little it impressed me, but how different with Mamma.”

I would love to have been able to hear these conversations between Graham Bell and my great great grandmother Anna L. Henry in 1876. What fascinating applications did they realize would come of the abilities to instantly communicate over distance? In their conversations did they dream of one day sending motion pictures (television), written letters (faxes and email), or possibility the entire internet? Could they even imagine such things back in 1876!

But what also struck me was how different my great great grandfather’s reaction was to Graham Bell’s invention. He wrote about the early telephone, “how little it impressed” him, thinking it was just a “plaything.” Of course later in his life, I think he was struck by the importance of what he saw in 1876, but not at the time.

I always hoped, that like Anna, I would be fascinated when I saw an important invention for the first time. That I would see, like she did, the possibilities in science, the revolutions it brings in understanding, and how it would lead to something greater beyond a single generation. I laughed at the foolishness of my great great grandfather.

But I remember the first time I was introduced to email. A computer science friend of mine got me signed up, using the Pine system developed at the University of Washington. I wrote in my journal that day, that I would not use it again, as it was complex, and I had no one other than my friend to write to. Only a few years later, I would be daily using email, and still do. Why had I not realized that email would change my life, and have such a big impact on the world? Since then I pledged to think more about not just the personal impact an innovation will have on me, but how it will impact the world.

United States politicians, particularly on the House Committee on Science have voiced a strong desire to have more political control of science funding in the United States. Furthermore, the amount of funds available for scientific research has not kept pace with inflation and the rising cost of doing science. And science funding in the last four years has fallen.

Non-defense Science Funding in the United State of America since 1953.

If we are expected to make scientific break throughs, having politicians dictate what should be funded and not funded, we are doomed in viewing key discoveries as just “playthings” rather than the scientific revolutions they truly represent. We underestimate the power of science because we only view it within the limited scope of the practicality of our lives, rather than the implications discoveries will have on future generations. Even the experts are poorly equipped at envisioning the future. For every scientific discovery I learn about, I remember my great great grandmother Anna, and the excitement she exhibited in 1876. I hope that 150 years from now, my great great grandson would read that I was excited by the possibilities of tomorrow’s next great scientific discovery.